Science Fiction - The Genre of Possibilities

- Mar 18, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Jul 2, 2025

In the first essay this month, I discussed the concept of genre, defending it from some common criticisms and exploring why it matters. The rest of the month, I’m looking more deeply at specific genres, and asking certain questions about each one. What it means, what it includes, and what kinds of decisions lead to its summoning.

This week, I’m talking about the genre of science fiction, and the trends and themes I have noticed within it throughout my own sci fi reading.

In some ways, analysing the genre of sci fi is an extension of my analysis on fantasy – I could describe the two genres in similar ways. They are often described and envisioned as being two sides of the same speculative coin, both focusing so intently on worldbuilding, and in this way are both very imaginative genres.

But whereas fantasy throws many things to the wind, such as the laws of our universe, and focuses purely on that imagination, letting that drive the creative decision (at least, as long as we’re talking pure fantasy), sci fi has a little more grounded of a process.

The important element here is that first part of the genre’s name – science fiction.

Sci fi is scientific in the same way real science is. It uses what we know of the real world (or, well, universe) as a basis for exploring what is possible. Not counteracting the laws of our universe but exploring them directly. The genre is essentially a series of what if questions – what if this happened, what if it developed in this way, what if this one difference took effect, what if those effects changed one of the laws of our universe… and so on.

In short, sci fi is the genre for exploring possibilities.

Of course, ‘possibilities’ is a broad idea. And science is too. Are we talking biology or physics? On Earth, or somewhere else? What somewhere elses are even possible?

Earth-like planets? Totally different planets? Maybe even a completely different universe. That’s just talking about space. What about Time? Past, present, future? Hell, maybe you’ve discovered or even invented a separate dimension, and you’re going to explore its own set of possibilities.

All these things are still scientific and grounded in the things we know. But they drive a story to a wide range of places. Some are more realistic – present day Earth, using the science and technology, not to mention knowledge, we have today, here, right now.

Other stories want to go wild, go way more imaginative – possibly stretching the definition as far towards fantasy as it will go while still staying true to the science. Or maybe it even includes fantasy as one side of its genre identity.

And just like with fantasy, there is a heavy dose of worldbuilding included with that identity too. Your typical sci fi authors aren’t going to stop at a single advancement or discovery and leave it alone. Rather, they want to explore every possible effect this new entity can have on the world as we know it. While it can be about the past, sci fi is much more interested in potential futures, and even when viewed through a historical lens, it’s usually still about the future – like Steampunk’s tendency to explore futures that could have been.

How does it affect technology? How does it affect the science itself? How does it affect the immediate environment?

These are the questions leading to a similar sort of worldbuilding that we would see from the fantasy genre, but with a more modern, scientific skin. It’s the kind of worldbuilding that leads to robotics, space travel, time travel, teleportation, cloning, alien races from another galaxy. These are the kinds of stories sci fi is most excited to tell, and importantly they are all based in the things we already know, and the kinds of effects we already know these kinds of discoveries and advancements can have.

The most important effect though, is the one it can have on society – on people and, in the case of fiction, the kinds of effects it can have on characters.

Because just like with the fantasy genre, science fiction receives much criticism for being mere speculation for the sake of mindless, shallow entertainment. And just like with the fantasy genre, these criticisms are totally baseless.

It’s worth spending a moment to talk about some of the other things sci fi stories tend to include. Because it isn’t all about the discoveries and advancements themselves. That would be like saying fantasy is only about the dragon, ignoring the people being eaten by it. No, sci fi is also about the characters who make those discoveries and advancements. Evidence of this can be seen through several of the genre’s other tropes.

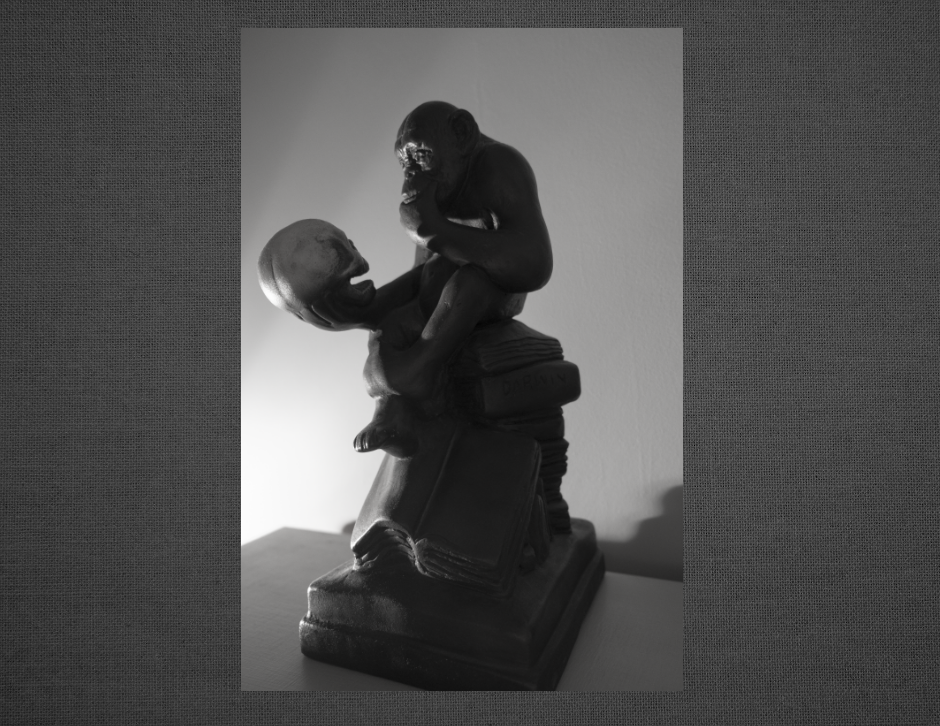

The mad scientist, the inventor, the astronaut. It is often through these characters that a sci fi story begins, and as a result, it is the effects the scientific advancement has on them specifically that is first explored. For instance, the triumph of their success, or their horror at what they’ve created. It can also be more passive effects, for example the accolades laid on them or, more interestingly, their exile and scorn. The ways other people react to what they have done, or discovered.

However, sci fi is also interested in exploring the effects to be had on regular people, outside of those fields of science. Because ultimately when everything goes wrong (as it usually does and, in truth, must for the sake of a good story) it is those regular people, like you and me, who are affected.

Because when the mad scientist’s accidental creation goes on a rampage, it is those regular people who must run, fight, or die. When the technological advancement malfunctions, it is those regular people who are caught in the blast. And when the astronaut inevitably brings back alien invaders, it is regular people who are being invaded.

If the scientists and inventors are comparable to fantasy heroes, it’s interesting how much more of a role greater society plays in sci fi. While fantasy will often depict these people on the outside, or perhaps as a reader insert who eventually becomes another of the fantasy heroes, sci fi must bring them in more directly, without turning us into something we’re probably not.

This is another example of the way sci fi is more grounded. Not only because of the scientific element of the genre’s formula, but because of the more integral role society plays in the tale. This focus on character is integral to all stories of course, but while fantasy inevitably draws from fantastical characters, the more grounded nature of sci fi leads to it drawing from more grounded characters.

Neither decision is inherently better or worse, of course. I’ve already gone into detail about the benefits and value of the fantasy genre in last week’s essay. And besides, certain subgenres of fantasy can be grounded also. That said, whereas fantasy can be grounded, sci fi is usually grounded, at least based on the stories I’ve found, and the role of regular people in the genre of science fiction does lead onto that other important element of this genre’s value, since it is their role which inevitably leads to the story exploring the effects that scientific advancements have on society as a whole.

Technology, transportation, economy, business, art, culture, politics, communication, warfare, agriculture, service… I could go on.

This is the more grounded worldbuilding of science fiction – the science and technology, and the ways they affect society and other people. But there’s another value of science fiction, and that is the way it can affect real science, technology, and society, in our own world.

One famous example of this is Asimov’s work on ‘I, Robot’ in which he created the word robotics (meaning, the study of robots) for the first time, without even realising it was a new word.

A more interesting aspect of that novel though, is the three laws of robotics – the regulations all robots must adhere to, stopping them from harming humans or allowing them to be harmed, while also retaining their usefulness as both machines and workers.

I don’t think real roboticists and engineers ever use these laws specifically, and in fact, the book itself is an analysis on every possible way these laws might become problematic, and need ‘robo psychologists’ and engineers to solve the issue.

But the important thing is that Asimov broached the topic with his fiction. He imagined the creation of a thing, in this case a robot, a possible development that might come into place around this creation, the three laws, and then explored the inadequacies and impacts both the invention and its regulations have on society, like the workers and families living around those robots.

Regardless of whether any of Asimov’s specific ideas come to fruition, the general idea will have notable impacts on technology moving forward. Already, there are articles written on how people will be protected from these more advanced pieces of technology, drawing from Asimov’s work to come to their own conclusions. And indeed, the concept of robots and automata in general first arose within fiction (such as the bronze giant Talos from Greek mythology) before humans ever seriously considered creating them for real.

And it’s not merely robots and AI for which all this is true – consider the wealths of alien fiction in which the very concept of life, and sentience is analysed, subverted and deconstructed on the regular. What life might be out there is a frequent topic of discussion, both casually and scientifically. I’m not going to tell you all our science fiction aliens are really out there… but some of them might be. And in any case, it’s the more general ideas that makes this significant, not the specific details. The debates and exploration of the potential and possibilities of what life is and can be – that’s an aspect of real science, both for our world and other potential worlds out there, as much as it is an aspect of fictional science.

Of course, it’s not merely the idea of science fiction becoming science fact that makes the genre important – there’s also the way it can help us explore our own current reality in more figurative ways, just like the fantasy genre does.

For instance, casting the extra-terrestrial alien character as a figurative exploration for fully Earth-based prejudices. Or using a specific, fictional technological advancement in order to explore such advancements in a more general way, as well as how we are now, or might be in the future, affected by such things. Or how humanity might cope if and when we are forced to reconsider our home planet.

Regardless of exactly how each specific sci fi story establishes itself, or what its individual goals are, the power of science fiction lies in its ability to do three things:

It is the genre of possibilities, letting the writer and their readers explore potential futures through science and technology in a host of different forms.

It can influence real science and technology and their developments, if not in a specific way, definitely in a general sense, and keeping discussion alive.

It uses things that are only potentially real to explore things that really affect us, by drawing comparisons or gazing into the future.

And that is powerful. That is important.

That is another thing about genre that is worth celebrating.

…

Next week, I’ll be exploring the horror genre through this same lens – meet me back here then, and let’s see what we can learn from those stories.

Comments